Transporting America: Current Policies Shaping Nation-Wide School Transportation

The State of School Transportation

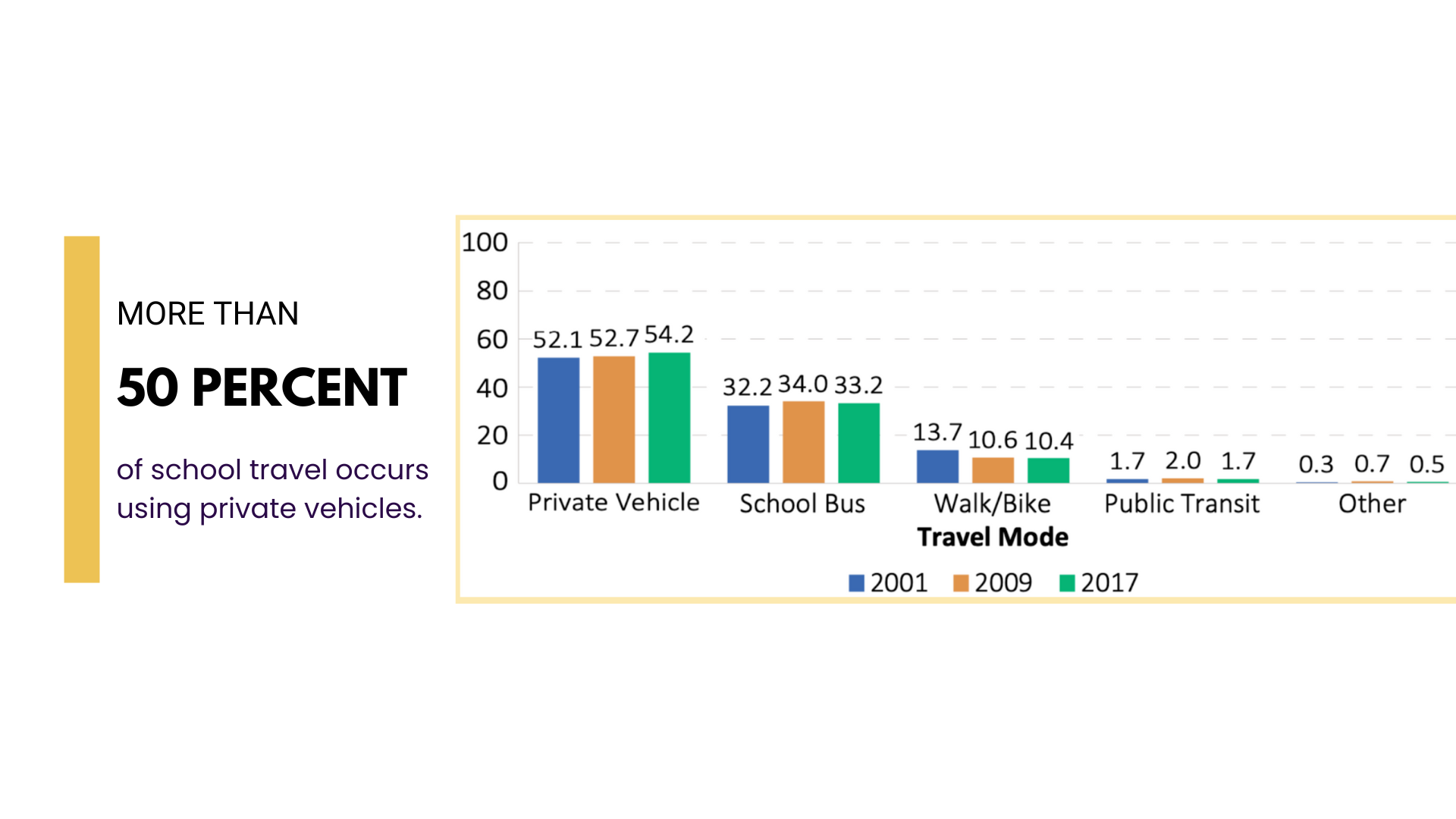

Over 25 million students, or 55.3% of the US public student population, ride one of 475,000 school buses each day. This is a decline from a high of 60% in the 1980s (Vincent et al., 2014). This decline can be attributed to modern social and policy challenges.

School choice programs

School choice programs are programs that allow funds for students to follow them to institutions that they and their families choose for them, whether it’s a public, charter, magnet, or private school (EdChoice, 2024). This is extremely applicable to the school transportation industry. In fact, state legislatures nationwide expect student transportation will play a role in the overall success of school choice programs. With more school systems moving from the traditional system of assignment based on geographic location and towards school choice, busing is no longer confined to a specific small zone of students, rather having to reach across cities and counties to be able to bus all students who desire busing (Vincent et. al, 2014). This increases private vehicle use. A study in Eugene, Oregon, showed that students attending choice schools were more likely to be driven to school (Yang et. al, 2012). As students opt to attend schools outside of their immediate neighborhoods, often based on non-geographic factors such as academic reputation or specialized programs, transportation routes become more complex and costly to manage, This makes routing an increasingly complex process, and the extra work, time, and gas expended on it has made it more expensive. (Vincent et. al, 2014) This is compounded by the hurdles districts already face pressure by parents to solve in the transportation sector, including a shortage of bus drivers, bus-ride harassment and bullying, accommodations for students with special needs, etc., issues that only threaten to worsen across longer distances. It also poses extreme financial challenges, as a full school choice system threatens to increase transportation costs by almost $200 per pupil, an increase of 34 percent, seen in New Orleans by Tulane University researchers (Gross, 2019). This trend disproportionately affects marginalized communities, particularly BIPOC and low-income populations, who face greater barriers to accessing preferred schools, especially as academically reputed schools continue to be placed in wealthier neighborhoods. This leads to a cycle where districts with the most BIPOC students receive substantially less revenue — as much as $2,700 per student. In a district with 5,000 students, this means $13.5 million in missing resources (EdTrust, 2022).

Efforts at bridging this gap have been sparse. Of 44 states who have enacted charter laws, only 14 explicitly detail the degree of responsibility the schools have for transportation, 13 require a “plan” of furnishing – yet not guaranteeing in any form – transportation for students, and just three require a similar standard of transportation for charter schools as public schools (Gross, 2019). However, as most of this legislation does not spell out the degree of mandated support, vary widely across regions, and often faces commuters from all around the area instead of a centralized location right outside the school, this legislation has not solved the increasing disparity in school transportation.

Policy changes such as implementation of enrollment zones that function similar to base schools yet give students a range of options within one geographical area are proving to be promising solutions. Ridesharing companies are also starting to make a surge in areas especially impacted by complicated school-choice programs. These services are usually privatized van or car services with highly vetted drivers, relatively high-cost providers that cities cannot use at scale (Vincent et. al, 2014).

School consolidations

Hand in hand with school choice programs, school consolidation programs tend to collapse smaller schools and districts into one bigger school or district. In fact, in the past fifty years, the number of public school districts has declined drastically in the United States, from over 40,000 to under 14,000 (Smith & Zimmer, 2022). This ultimately leads to the same issues as school choice programs and has an additional equity problem. With school consolidation, base schools can start being placed further away from students, leading to another complex routing and funding problem for buses. This has the additional aspect of “geography of opportunity”, as these transport barriers influence the opportunity gap (Vincent et. al, 2014). The quality of schools tends to generally increase the further away from rural, low-income, and minority neighborhoods. This means the transportation disparity is the largest for those neighborhoods, with logistics affecting them the most and taking the heaviest toll on their attendance. With school choice programs, this only worsens, as higher-income students can afford to flock to better locations for better schools whereas lower-income students are left behind in schools that undergo a vicious cycle of losing funding, having poorer outcomes due to a lack of educational resources, and then losing funding because of poorer outcomes. This takes a heavy toll on the transportation routing rural communities are afforded, leading to decreased school attendance.

Transportation regulation

The regulation of transportation systems encounters multiple other challenges stemming from the involvement of various levels of government, each with its own set of regulations and policy priorities concerning transportation. Local, state, and federal governments may have different ideals for transportation. Funding limitations necessitate complicated trade-offs regarding resource allocation. Rising operational costs, coupled with evolving transportation needs and logistical challenges, have led many school districts to explore alternative cost-saving measures of transportation, such as transportation fees or outsourcing to private operators. In fact, it is this influence of a robust private sector, reinforced by policy incentives, that demonstrates how transportation regulation is balanced with the priority of preserving the private sector. Additionally, concerns voiced by parents and guardians regarding the safety and reliability of transportation options complicate the process of standardizing regulations. The bus industry maintains yellow buses are the safest for abductions and only 2% of all fatalities. Yellow buses do limit the amount of students walking and being exposed to traffic as well as decrease the traffic and ensuing particulate matter in the air. However, peer reviewed research hasn’t proved any substantial difference from regular public transit in terms of safety, posing a dilemma for school districts when faced with the fact that returning to in-house services would be 15-20% less expensive (Vincent et. al, 2014).

Public transit

With all of these factors to consider and amidst growing concerns over traffic congestion, environmental sustainability, and equitable access to transportation, there is increasing emphasis and nationwide curiosity into investing in public transit infrastructure. This investment aims to bridge the disparity in “geography of opportunity” by reaching out to residents of isolated neighborhoods who may lack access to reliable transportation options to reach higher-quality educational opportunities available in other areas. In light of this option, it’s worth noting that the legal framework surrounding student transportation varies widely across the US, with differing reimbursement programs, bus mandates, and regulations. An ever-present measure is the Tripper rule, which restricts the use of federal transit funds for student transportation in order to preserve states’ rights and the private busing industry. This regulatory variation often requires school districts to navigate a whole other landscape of funding and regulatory challenges.

Certain case studies exemplify public transportation solutions to bussing. In Oakland, California, initiatives aimed at increasing youth access to public transit have been instrumental in addressing transportation barriers. The subsidized youth bus pass program offers a transportation option for students, with a daily fare of $1.05. However, as compared to the country-wide average of 55.3%, only 23% are estimated to utilize the program. In Washington, D.C., efforts to subsidize student transportation costs during commuting hours have yielded positive outcomes. Portland, Oregon has implemented completely free bus passes for students.

A public transport solution comes with its own challenges, however. Firstly, the degree of subsidy varies wildly across the country. Urban areas are more likely to see the value of transit and invest into higher degrees of subsidy, meaning efficient coverage options for student transportation would be even more variable moving to public transit transportation. Second, proof of eligibility for public transit subsidization is a complicated process. Certain systems such as the one in Washington, DC have an age cut-off at their school district’s maximum high school age, usually 22, which can end up invoking a free rider problem for those who aren’t students but still fall within the age range. This means systems of manual checks must be conducted during hours of commute. This may be in the form of proof of enrollment checks or technology to track and restrict the number of trips per day for student riders, the latter of which would be a sizable technological investment. Furthermore, all this must carefully cater to Tripper law loopholes. There can be no adjustments to the routes, any designated vehicles, or any decrease in accessibility to the general populace.

Additionally, it poses questions of convenience for students themselves. While public transit may be a way to maximize parent time and provide relatively – if not completely – affordable daily transportation, research in New York shows that the average commute to school increased from 15 minutes to 29 minutes with the use of public transit. Traditional yellow buses are the least time-efficient for students, with the median commute for students being 35 minutes up to upward of 90 minutes one way. This efficiency gap does have a profound effect on private transportation rates. While New York’s public transit rate remains high – perhaps due to the fact that it remains a common form of transportation overall – in cities like Denver and DC with strong public transportation systems, as many as 67% of Denver parents and 43% of DC parents drive their kids to school (Vincent et. al, 2014).

Conclusion

School busing serves as a large component of the transportation of America’s schoolchildren. However, the complex landscape of school transportation in the United States reflects broader societal trends and policy challenges. The decline in school bus ridership, driven by burgeoning school choice programs, financial/regulatory challenges, and school consolidations, has exacerbated transportation inequities, particularly for marginalized communities. It has raised questions about the efficacy of the “yellow bus” as an accessible, preferred, and economical bridge to the transportation gap. Efforts to address these challenges in a public capacity have had varying degrees of success across different states and regions. Ultimately, achieving equitable student transportation requires efficient policy frameworks within school systems and innovative solutions.

References

- Gross, B. (2019, August 6). Going the Extra Mile for School Choice. Education Next. Retrieved May 2, 2024, from https://www.educationnext.org/going-extra-mile-school-choice-how-five-cities-tackle-challenges-student-transportation/

- Meko, T. (2017, February 2). Student Transportation and Educational Access. Urban Institute. Retrieved May 5, 2024, from https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/88481/student_transportation_educational_access_0.pdf

- School Districts That Serve Students of Color Receive Significantly Less Funding. (2022, December 8). The Education Trust. Retrieved May 1, 2024, from https://edtrust.org/press-release/school-districts-that-serve-students-of-color-receive-significantly-less-funding/

- Smith, S. A., & Zimmer, R. (2022, February). The Impacts of School District Consolidation on Rural Communities: Evidence from Arkansas Reform. EdWorkingPapers. Retrieved May 18, 2024, from https://edworkingpapers.com/sites/default/files/ai22-530.pdf

- Vincent, Jeffrey M., Carrie Makarewicz, Ruth Miller, Julia Ehrman and Deborah L. McKoy. 2014. Beyond the Yellow Bus: Promising Practices for Maximizing Access to Opportunity Through Innovations in Student Transportation. Berkeley, CA: Center for Cities + Schools, University of California

- What is School Choice? (n.d.). EdChoice. Retrieved May 18, 2024, from https://www.edchoice.org/school-choice/what-is-school-choice/

- Yang, Y., Abbott, S., & Schlossberg, M. (2012, January 5). The influence of school choice policy on active school commuting: a case study of a middle-sized school district in Oregon. Wikipedia. Retrieved May 18, 2024, from https://darkwing.uoregon.edu/~schlossb/articles/Yang_EPA.pdf